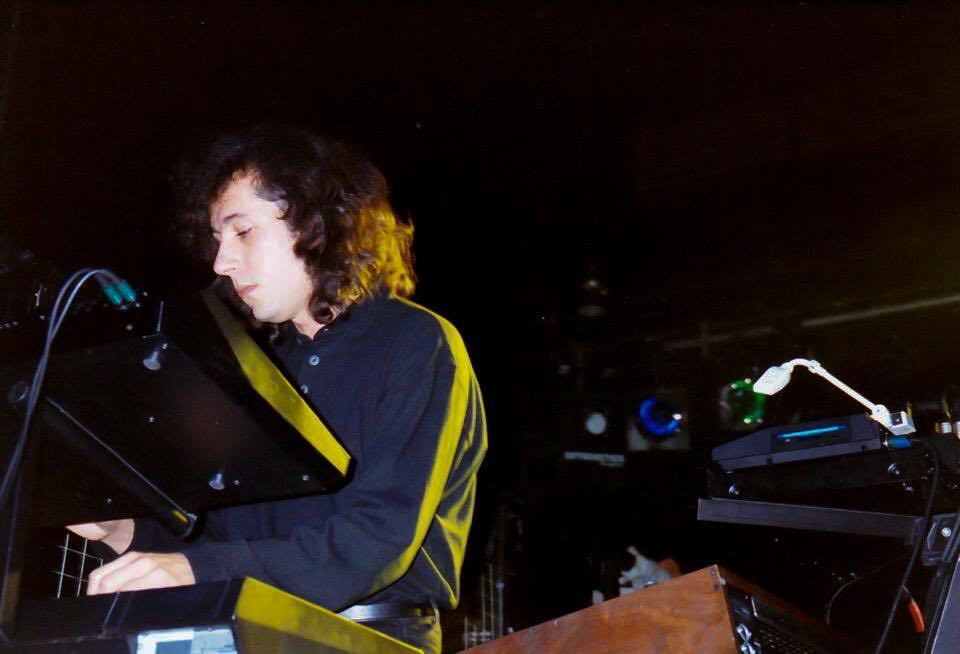

Originally serving as Henry Fool’s keyboardist, Stephen Bennett soon became a key collaborator on Tim’s various solo albums, as well as serving as a member of the No-Man live band in 2008 and 2012.

How did you first hear about No-Man and how did you get involved with the making of Together We’re Stranger?

I come from the North West of England like Tim and I’d heard one of his early bands on Radio Piccadilly in Manchester, while he knew me through my involvement with the NeoProg band LaHost and my music technology writing. I’d also bought some No-Man records, so I was familiar with their work, and I vaguely recall that Steven was around at the Marquee club in London when I spent a lot of time gigging and ligging there in the ‘80s. Tim played in Norwich with Samuel Smiles and a friend, Richard Fryer, mentioned he had actually moved to Norwich so he set up a meeting. Tim and I got on really well straight away as we have much in common, with similar backgrounds and artistic likes and influences. As for working with No-Man, Tim is incredibly generous — he’s always creating opportunities for his friends to shine, so it was inevitable I ended up working with them.

How did you make the noise that opens the title track of Together We’re Stranger?

I was living in Sweden at the time, so it probably involved either Moose mating calls or some experimental synthesizer I was reviewing. All I know is that it’s probably the most hated moment on any No-Man album. Perhaps, the most hated moment on any album ever released.

What was the impetus to start Henry Fool?

Richard Fryer proved to be a perceptive individual as he accurately predicted our shared interests and Tim and I quickly delved into passionate discussions about jazz and progressive rock. Surprisingly, we discovered that we had come close to crossing paths on several occasions at various music industry gatherings. We began entertaining some rather outlandish ideas for a ‘fantasy’ concept album based on the novel Stig of the Dump. However, our enthusiasm quickly waned when the author of said book, Clive King, happened to sit down at a nearby table. We took this unexpected encounter as a sign, but we departed with a determination to collaborate in some way. A few months later, Tim and I found ourselves at Paul Wright’s Music Farm studios in Norfolk as Tim and I insisted that a substantial portion of the album be recorded live as a band. Thus, Henry Fool was born, and our collaboration began. I hope we do make another Fool album as we do have a lot to say still in this jazz/prog format. Henry Fool was also my first collaboration with Steven who mixed a couple of tracks alongside my mixes.

How would you say Tim has evolved as a songwriter over the years of your collaboration?

I think he’s technically more confident now, which has allowed him to experiment more. Tim is a restless creator, always exploring new ways of making music and expressing himself. He chooses his collaborators well—I mean, look at some of the amazing people he’s worked with on his albums!

Tim has said that he was disappointed with his first solo album, My Hotel Year. Is that a sentiment that you share?

I never really liked the ‘cold’ and sparse sound of the mixes—but the songs and performances are great. David Picking, who mixed it and plays drums and other stuff, is an amazing musician and technologist and he did a fantastic job. I think the album is pretty unique sonically and musically. I tend to like the warm and overblown, so it was never going to sound right to me, but it’s still an amazing album. I thought the songs I co-wrote with Tim are pretty good, especially Sleepwalker and working with David Torn, Hugh Hopper, Peter Chilvers, the Enos and David was a brilliant experience.

What were the rehearsals like for the 2008 No-Man tour?

Imagine the most fun you’ve had and double it! Steven was away for the first few rehearsals, so the rest of us set up at a room in Cambridge—we sounded pretty good straight away I thought. Then Steven arrived with a pedal board the size of a bus! As soon as he hit a chord, it just took the music and performance to another level. I was using an early version of Apple’s Mainstage and planned to take that on tour with a Mac and a master keyboard—I like to travel light, though my studio is packed with vintage gear. All the way through rehearsals, my Mac kept crashing and Tim and Steven were starting to look nervous. I, of course, boasted that it’d be ‘alright on the night’, but the band were doubtful. As it turned out, my computer was probably the only thing that didn’t break on the tour. As for the tour itself, it was brilliant. The band were all similar in our tastes and lifestyles and most of us spent the time arguing about important stuff like which was the worst Mike Oldfield album or if any of the post-Duke Genesis albums were any good. Think Tim and Steven’s podcast, but with a whole band arguing instead. I just wish we’d recorded the last gig rather than the first for Love and Endings though, as we were, if you’ll pardon my French, shit hot by then.

How would you say the live band has evolved between the short 2008 tour and the longer 2012 tour?

When you play together a lot, a kind of telepathy develops between the musicians. You can relax and take the music into new areas and take chances you might not at first. Working with brilliant musicians is one of the best experiences you can have, and Tim and Steven both really encourage you to push the envelope of your creativity.

How would you say the arrangements of tracks differed from the studio to live performances when it comes to your role as keyboardist?

I’m a great believer in not just replicating the recordings live, though I know that fans often are disappointed by this. Inevitably, it was louder and rockier than the albums. I play less stuff live as well, as I want to have some fun on stage, not just be concentrating on pressing buttons or doing anything particularly technical. So, the arrangements tend to be sparser yet more powerful than any recordings.

Can you shed any light on the aborted 2012 No-Man album? How much of Abandoned Dancehall Dreams was originally supposed to be for that album?

I’m not totally sure, but Steven was encouraging Tim to continue to develop his own oeuvre at that time. And Steven was really busy on his solo work, of course.

You and Tim haven’t co-written together since 2017’s Lost in the Ghost Light. Why did you two stop writing together, and might we see the two of you collaborate again in the future?

My son, Dexter, was born in that year so I took a hiatus from gigging and Tim’s moves to the west country meant we don’t meet up as much as we used to. And there was the pandemic of course! Tim and I also took the opportunity after four albums together to pursue different musical avenues and to work with other people. He did ask if wanted to do some work on Love you to Bits, but I decided that it really didn’t need my input—sometimes doing nothing is the best artistic choice. I’ve also been busy, working with members of White Willow, Airbag, Änglagård and Rain (Jacob Holm-Lupo and Ketil Vestrum Einarsen, Björn Riis and Mattias Olsson—with John Jowett (IQ, Arena, Tim’s band) and Myke Clifford from Henry Fool) in the Anglo/Scandinavian band Galasphere 347—our second album is due out in 2023—and I’m recording an album that might finally satiate my love of the ‘70s and ‘80s British Jazz scene, with Theo Travis on sax, Mattias on drums, John Jowett on bass, and the fantastic Nick Fletcher from the John Hackett band on guitar. I also get to write for a brass section, which I’ve been meaning to do most of my professional life! Tim and I speak on a regular basis and I’m sure we’ll work together again soon—I just need to get around to sending him some ideas!