Steven Wilson is a man who needs little introduction in the world of No-Man. Producer, singer, songwriter and multi-instrumentalist, his list of projects and releases both under his own name and with the various bands he’s been a part of run the sonic gamut from ambient drone to art pop to progressive rock.

Steven was kind enough to take time out of his busy schedule for a live interview regarding the history of No-Man from his perspective.

What were your first impressions upon meeting Tim Bowness and how do you think he’s evolved as a songwriter?

Oh, wow, that’s a long time ago, isn’t it? So I first met him in 1987. He was and is three years older than me. And when you’re 19 years old, as I was when I met him, that is a big thing. He’d read more books than me. He’d heard more music than I had. He became a little bit of a mentor, introducing me particularly to a lot of music that became very important to me. So I definitely was very impressed with his knowledge, how articulate he was, his intellect. All of those things were very inspiring. But above all, I think the thing that we bonded over the most was this kind of open minded curiosity that we both shared. In the sense that nothing was out of bounds when we when we first started making music, as I’m sure you’ve heard the story before, the first session we did together, which wasn’t the first time we met, it was the second time we met. But the first session we did together, we produced in the space of two hours a sort of fairly pompous piece of ambient progressive pop, a three minute slice of industrial funk and a kind of gothic ballad. It was almost like these were all things that we could we were equally enthused about.

I’d never met anyone like that before who kind of shared my curiosity for the magic of music wherever it lay. There were no parameters. There was no idea of limitations in this. Still not when we work together. Which, of course, is a very uncommercial perspective to having them in the music industry. Music industry expects you to find a formula and stick to it. And I think that’s why I myself and Tim in a sense stood out in the industry a little bit, for better or worse.

How much of an influence would you say Tim has been on your own journey as a songwriter?

When I first met him, I wasn’t really a lyric writer. I wasn’t interested in writing lyrics, but I definitely was very impressed with his lyrics, his sense of poetry, his sense of prose and the way he would draw on the worlds of literature, cinema, life experience and sometimes trivialities to become fundamental to a song. I think some of those early No-Man song titles came from conversations, sometimes quite trivial things Tim would latch onto and it would become a song, a crystallized moment if you like, in everyday life that somehow reflected back at you something profound and that something I was getting this also from reading at the time and also cinema. Tim definitely had that down, that kind of approach to to songwriting and lyric writing and made me aspiring in a way to be a lyric writer and to be a better lyric writer.

One thing I found in my research were three releases that were called Strip Wild, Death and Dodgson’s Dreamchild and Prattle. Can you shed some light on these?

I think I don’t think any of them came out. They were probably just all titles for things that we planned to do. Tim was always coming up with titles, as it’s part of his job. I would probably latch onto a title and say, “Yeah, that’s going to be we’ll do an EP, you know, and we’ll put this song on.” Then we would probably fail to get a record deal, so we never managed to put it together or release it. They were probably they were just all working titles for EPs or combinations of songs.

How do you look back on those first two No-man albums, along with singles and all the events surrounding them. Do you think they were successful albums in your eyes?

I’ve gone back and remastered them recently for this prospective box set, and I have to say I was pleasantly surprised. Time is a great healer and distance gives you a more fond perspective of things. I found this with a lot of things in my life, things that I was kind of embarrassed about at the time. I can now listen to it as something that was almost made by someone else. I can appreciate it. There were songs that I just didn’t remember at all and when I was relistening to them I thought, “This is really good.” While there are some pieces I still cringe a little bit at, I would say 80 percent of it sounds really good to me. What I realize now is how alien we must have sounded in the contemporary music scene at the time. The funny thing is we felt like we were part of what was going on, but now I realize we were a million miles away. It was in a good way but in way that perhaps made it hard for us at that time.

I think songs like “Days In The Trees” and “Sweetheart Raw” on the surface have the elements of what was going on, such as the use of beats and a sort of dance rhythm, but everything else about it is completely different. It’s unashamedly romantic, unashamedly lush, unashamedly ambitious, epic and textural. It also doesn’t have the archness that I think a lot of the other sort of electronic pop crossover music had around that time. We were closer to the Pet Shop Boys than we were to The Happy Monday in that respect. I can appreciate now how different we were and how the sound is very unique, largely because of Tim’s voice. There’s also the violin, which is a unique element to the musical vocabulary. Some of the production and the sounds are a bit primitive but even that in a way gives it a charm that I couldn’t have appreciated at that time.

They’re almost, in a way, the future echo of what was to come with the idea of combining very epic textual balladeering with electronic sounds and a nostalgic, almost literary quality to the lyrics. That would would eventually become the blueprints for what was to come on later albums like Together We’re Stranger and Returning Jesus.

How much say did you and Tim have in the regards to the choice of singles and direction of music videos?

Well, I’d love to tell you we didn’t have any, but we did. We had a lot of control. We wanted to get a foothold in the industry such that we could continue to do this for the rest of our lives to make pop music and get paid for it. And to do that, realistically speaking, you need to have a breakthrough of some kind. The first couple of singles got phenomenal press, but didn’t really sell. We were persuaded, very easily I might add, that we needed something more radio friendly. So we set about writings songs to order. I have to say, its the only time in my life I’ve ever done it. I only did it for about 18 months. I learned from my mistakes and have never done it again because it didn’t work. There’s nothing worse than failing on someone else’s term.

Can you talk a bit about the “Only Baby” music video?

It’s awful isn’t it. It’s probably the only time we’ve ever spent a lot of money on a video. I think we did the “Colours” video for five hundred quid but “Only Baby” was something like ten grand or so spent on it. I think “Only Baby” was a great pop single, notwithstanding the terrible video. I don’t feel any mistakes were made in the choice of single, but the video was horrendous.

Several No-Man tracks seem to reuse elements or chord progressions that show up elsewhere in your work. For example, the sampled flute from “A Plague of Lighthouse Keepers” is on both “Voyage 34” and “Sweetheart Raw.” Do you find yourself reusing elements from previous songs a lot?

Nowadays, not so much, but at the time I was basically making music almost all the time without necessarily thinking about who it would be right for. I would sometimes write something for Porcupine Tree and think to myself, “Oh, I wonder if Tim could come up for some lyrics for this.” I’d send him the backing track and then he would come along and we’d rework it as a No-Man song. The best example of this is with “Days in the Trees,“ which started out as a Porcupine Tree instrumental called “Mute.” I sent it to Tim and he wrote lyrics and a melody for it. I saw no reason to not release both versions. In a way I kind of like the conceptual continuity across my career. Another example of that would be the Bass Communion song “Drugged,” which became the basis for the first part of “Together We’re Stranger.” Those things are like little Easter eggs for people to discover.

What did you look for in the samples you used in the early No-Man and Porcupine Tree tracks?

Well, different reasons depending on what sample. I would have used them because I didn’t have access to a real flute player or access to Lisa Gerrard. It was kind of like trying to expand the musical palette by sampling. In that time, we’re about this in the golden age of sampling. Everyone was doing it from The Beastie Boys to DJ Shadow to De La Soul. I was listening to a lot of those records as well, records that are almost entirely made up of sampling or turntablism. We’d go crate digging and find these great grooves from 70’s soul and funk records. It was being a bit of a magpie in that sense, finding things that I could write music over the top of because I wasn’t a drummer, I didn’t have a drummer to work with, and yet I love good grooves.

I’d grown up with with great disco, funk and groove records, so I wanted to work with great grooves. Tim and I were massively inspired by Massive Attack at the time. A lot of their basic rhythm tracks were created by sampling, like famously sampling the Billy Cobham loop on “Safe from Harm.” We were kind of tapping into that aesthetic, the idea of doing some writing, finding some great grooves and writing our own song over the top. Others samples were just because I didn’t have access to the sort of musical colors that I wanted to have access to. Since I didn’t know anyone that played the flute or I didn’t know any female singers, I ended up sampling them instead.

Was it difficult to bring the material to the stage when you were performing as a trio?

It was really hard. I hated playing live for many years. Part of it was the struggle in trying to bring what were quite layered, complex productions into the kind of brutal environment of a live setting. The kind of places we were playing in those early days, places like small clubs and pubs, you can’t get across subtlety. It would have been like trying to play “Count of Unease” in a pub. It’s just the wrong context for material like that. I think we ended up just turning the volume up and relying more on the aspects of our sound that were a bit more rock orientated but were less interesting to us. Tim would always sing louder and almost over sing. It took me a long time to recover.

What’s the backstory behind “Heaven Taste?” How did it evolve into the 21 minute piece that was released as the B-side to “Painting Paradise?“

If I remember correctly, it was an ambient instrumental that I created for what I suppose might have been a really early incarnation of Bass Communion. I remember doing a lot of ambient instrumentals in the early 90’s with the idea that I was going to do a side project. I can’t remember whose idea it was to get JBK to work on it. The original instrumental was about 12 minutes long. The full 21 minute version was constructed by piecing together three alternate mixes of the same track. The piece in the middle with the hand percussion for example, that was originally buried under the main body of the track. I soloed it a created a kind of percussion based remix and edited that into the middle of the track. I kept doing these different mixes and eventually I had three mixes that I really liked. I edited the three mixes together to create the full 21 minute version

Between Tim’s own “Hard Drive of Doom” and your tape collection how much is left in the collective No-Man vault in regards to unreleased tracks?

I remember compiling two volumes of lost tracks. Just looking at the DAT tapes from 1990 to 1992 that I have here, there’s quite a lot of stuff. I don’t recognize some of these titles, which means they might be early versions of things that were released. Maybe some of these are just instrumentals that never got vocals added to them. I’d say there’s probably a good couple of CDs worth of unreleased songs.

What lessons did you learn from the early No-Man live shows that you took with you when you came time for Porcupine Tree to do its first few tours?

I don’t think it did. I think Porcupine Tree was such a different proposition right from the beginning. I mean, it was a rock band. No-Man hadn’t really worked the way we had wanted when we tried to do it live. Porcupine Tree was, at the end of the day, a conventional four piece rock band. There weren’t that many backing tracks. It was just four guys playing live together.

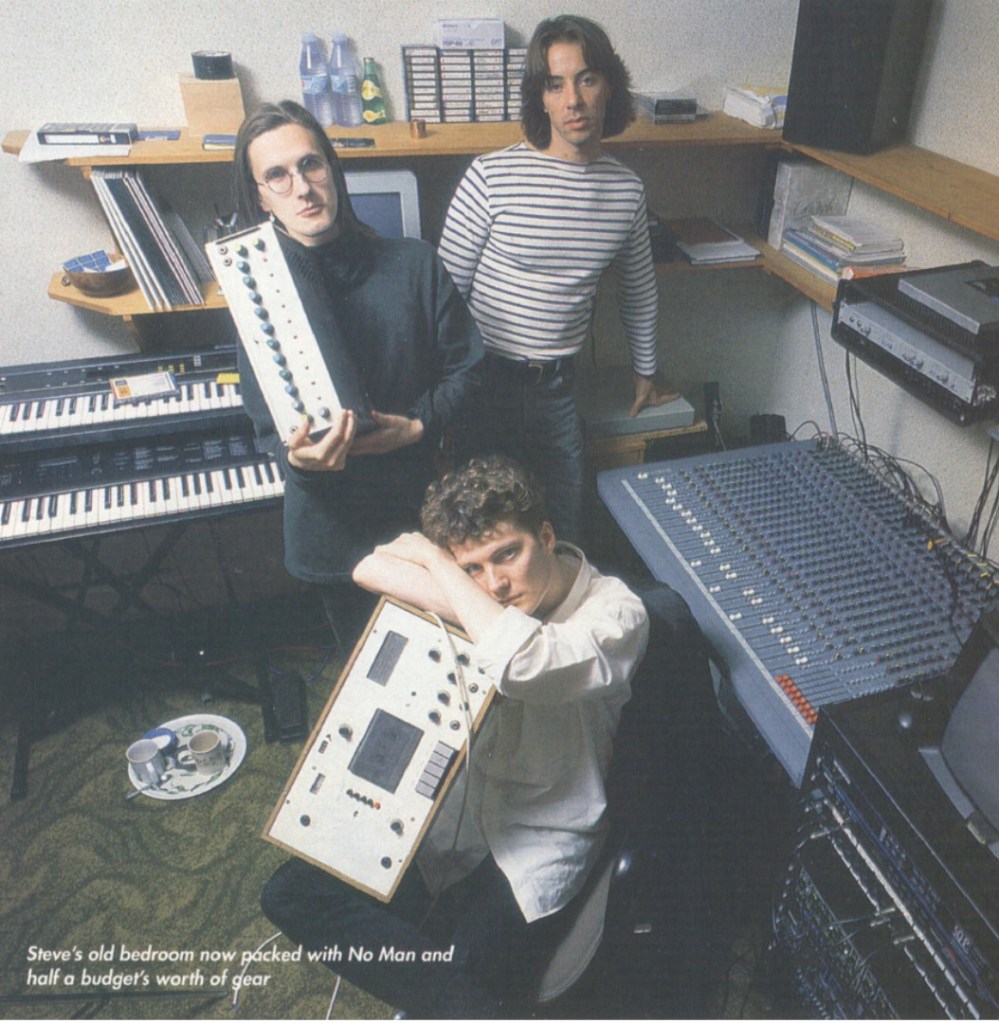

What was it like having Robert Fripp in your home studio to work on Flowermouth?

It was amazing! I remember being a bit embarrassed that he was sitting in my little bedroom studio with his big rig and his assistant sitting there, but he was lovely. Robert’s whole thing was just purely intuitive. He didn’t want to hear the song before. He said, “Just don’t play me the song, just roll tape” and he just would produce music. And of course, it was a real buzz for myself and Tim. He was probably the first musician that I think we met that we could honestly say we’d grown up listening to what they did. I think he stamped an incredible kind of signature on the album. Everything he did on that was recorded in a very short period of time, about a day or two. It was inspiring.

What’s your side of the story in regards to the departure of Ben Coleman?

I’m sure everyone’s memory is different. I think there were two things that would have contributed to myself and Tim kind of going it alone at that time. The first thing was, from my own personal perspective, I just didn’t want violin on every single song. This is part of the problem with having such a distinctive soloist like Ben. He’s an amazing musician, by far superior to myself and Tim in terms of musicianship. I was, however, becoming frustrated trying to integrate violin into every song. I didn’t want a violin solo on every song. I wanted to hear flute, saxophone or other sort of musical textures and other colours. You can begin to hear those on Flowermouth with the trumpets, the saxophones and the flutes. Ben was becoming frustrated because I was saying “You know what? I don’t want the violin, I want flute on this track” and, quite rightfully so, him saying, “Now hold on. I’m in this band, and I’m the soloist in this band. Why are we getting a flute player?” I just wanted to hear different musical forces that add different things to the musical vocabulary.

The second thing is that the band had not been successful. Let’s address the elephant in the room here. The first album had not been successful. We were struggling financially. I think we were offered by One Little Indian for Flowermouth a reduced advance, so we couldn’t sustain the band as a three piece anymore. That’s the brutal reality of it. We could not sustain the band as a three piece financially anymore, particularly having a member that didn’t contribute to the writing and was essentially a solo voice. I think those two things conspired in a way to unfortunately sideline Ben, as he had never been part of the connection between myself and Tim.

Why did you bring Ben back for the Porcupine Tree track “What Happens Now?” and the first show of the 2008 tour?

Well, the simple reason is he’s amazing. He’s an amazing soloist and if you’ve got a song where you think to yourself, “Wow, you know what this track needs? A scorching violin solo!” there’s no one else I would call. I’d say he’s probably the best rock violin solo player I’ve ever come across. Even though I didn’t want violin on every single song, there are times where I thought to myself, “That’s exactly what I need!” and Ben would be the person I’d call. He’s actually done a session for me quite recently for a new song.

What prompted you and Tim to do the hour long sessions of writing, recording and finishing a song that you two did for Wild Opera and Dry Cleaning Ray?

It was to change it up. The one thing that almost always works for me is to create a sense of limitations to function within and see how it affects what you do. It also was kind of a way to get our writing process kickstarted. The idea was we’re going to spend an hour on a piece of music. If it’s not working, we would just move on and start again on something fresh. It inspired us to think about music in a very fast and intuitive way. And it worked! We produced something like 20 or 30 pieces in two or three sessions. They became the foundations for the Wild Opera album, an album that we are still very proud of. I’ve done the same thing on THE FUTURE BITES, getting out of my comfort zone by putting the guitar down and saying, “I’m not going to work on the guitar, I’m going to work on the keyboards.” So things like that definitely revitalize and decontextualize the way you think about music and the way you create music.

Why was “Lighthouse” revisited for Returning Jesus after having first demoed the track in 1994?

I don’t think we revisited it. We had been working on that song relentlessly for about six years by that point Every year we do a different version of it, and I think the previous album Wild Opera had not been the right context for it. By the time we got around to Returning Jesus it felt like it belonged to that musical world. So I don’t think it was a question of revisiting in the same way as Love you to Bits, which is literally a song that we didn’t touch for about 15 years. “Lighthouse,” I think we were always working on it, developing different mixes, different versions, changing the tempo. So it wasn’t a question of revisiting. I think it was just a question of finally saying, it’s done after six years.

Why rerelease Speak in 1999?

We got offered a deal by this Italian label called Materiali Sonori that we both liked at the time. They asked us if we had anything that they could release. We said, “Well, what if we go back and rework and remix the Speak material?”

What caused the massive change in sound between Wild Opera / Dry-Cleaning Ray and Returning Jesus?

A lot of my career has been about me thinking, “OK, I’ve done that, what can I do next is different.” It’s always been that way with me and it’s the same with Tim. So we might have said, “Well, you know, we’ve done the Wild Opera thing, we’ve done the beats thing, we’ve worked with the rhythms and the industrial rhythms. Let’s go in complete opposite direction now and let’s do something really epic and romantic and texture and orchestrated.” It probably was us just trying to do something that was almost a reaction against what came before.

Together We’re Stranger is considered by many No-Man fans to the your best album. Was there a sense that you were working on something special during its recording?

I have that sense for every record I’ve ever made. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have carried on working on it. It would be a very depressing thought to think you were halfway through something and then start to think to yourself, “You know what? This is really isn’t that special.” I don’t think Together We’re Stranger felt any more special than Returning Jesus or Wild Opera. It’s only in retrospect that albums reveal their true immortality or not.

I would have thought, if anything the “songwriting” was probably more rigorous on Returning Jesus because the first half of Together We’re Stranger is almost like a tone poem. There’s very little in the way of conventional songwriting. I guess it’s one of those times when an album turns out to have a magic about it that you couldn’t really have contrived. It just has a magic. And that’s something that kind of revealed itself over a period of time to both us and the listeners.

Schoolyard Ghosts seems to cover a extremely broad range of sounds. Was it challenging to make that record cohesive and, as you mentioned in the In Absentia documentary, have a sort of cinematic feel with the track listing?

No, because those are the records that I like. Very often the records that I like the most are the records I feel have the most sense of cinematic sweeps. The analogy I’ve always used is when you when you’re watching a piece of cinema, and part of what makes cinema great is the the juxtaposition of mood. So you go from, for example, a scene full of joy and then something tragic happens. The next scene is very melancholic, very depressing and very sad. You don’t often have those kind of mood shifts within pop music. Songs tend to be either happy songs or sad songs. One of the beautiful things you can do across an album is you can almost program it to be like a piece of cinema by juxtaposing those scenes and those different emotions. I love doing that and I think it’s one of the things I’m good at. Schoolyard Ghost would have been another example of taking all those disparate elements and making it hang together in a satisfying way.

What was the process like to arrange the various studio tracks for the live performances when it came time to tour in 2008? Was it a challenge to translate the stuff you guys did in the studio onto the live stage?

I mean, it’s always a challenge. You make a studio record and you don’t set any limitations on your ambitions to overdub and create layers in the production, then suddenly you’re in a live context and you’ve got to somehow recreate that big cathedral of sound with a few live musicians. If I remember rightly we didn’t use backing tracks. It was completely live. It was quite a large band. We had six or seven people, so the possibilities were much greater than they had been, say, back in ’91, ’92, when it was just me, Tim and Ben. Back then Tim was struggling to get those vocal nuances over the sound of a live band.

How did the live band evolve between 2008 and 2012?

We had decided to get rid of the electronic drums and have a live drum kit, and that was so much better. Andrew Booker, the drummer, was using electronic bass, using pads and electronic drums which I found a bit unsatisfying. I love to feel having a live drummer behind me. Confidence would have also probably been much more prevalent a second time around. We knew it worked. We knew we could do it. I think the other thing worth mentioning here is it becomes more fun that the kind of careerist aspects were no longer relevant. In the early days, we were very much aware that we were trying to carve out careers for ourselves, trying to become financially stable, trying to convince journalists and trying to make friends and all those things. By the time we get around 2012, 20 years later, we’ve got a fan base. We just got to go out, enjoy it, have fun and know that there are people out there that that have been waiting for us to go out and play that music and the feeling like they’re on our side. That was the thing in the early days, it was always a battle to try and win over the audience.

What does the future have for you and Tim beyond the upcoming box set? Any chance of us getting a new No-Man album anytime soon?

I never rule these things out you know. I always have fun working with Tim. He’s a lot of fun to work with, obviously we have a good rapport and we are never short of ideas when we get together. It’s just a question of time. I don’t have the time to do all the things I would love to do. It’s an unfortunate reality that it kind of always gets pushed down the list of priorities for me, because it is something that is more of a niche these days. I’m also used to being the singer and songwriter in my projects these days. So going back to a scenario where I’m writing with someone else and I’m not the singer is slightly odd for me now, to be honest.

I was also able to ask Steven a few non No-Man related questions

How do you manage to balance your work as a musician, a producer and as a family man?

I think the answer is I don’t, and that’s why I’m doing a bit less than I used to. If you look at my output, say in 2011. I made a solo record, which is a double release, the Storm Corrosion album, I released the last Bass Communion album and I did a bunch of remixes. Now I look at the last five years. I’ve done two solo records and one No-Man record. For me now, it’s definitely about quality, not quantity. I want every record I make to be a major statement. So that means by definition, I think that means being a bit more selective about the music. I mean for THE FUTURE BITES, I wrote 30 songs and there’s only nine on the record. That was almost unheard of 10 years ago. Back then it would have been like, “Write 10 songs, put that out. Write another 10 songs, put that out.” It is a bit more of a reflective process now than I think it used to be.

Could we see Stupid Dream and Lightbulb Sun getting the same deluxe treatment that In Absentia got?

We are going to work through the 21st Century albums first, so that means Deadwing and then Fear of a Blank Planet. Deluxe editions of Stupid Dream and Lightbulb Sun would possibly be after the 21st Century albums.

What is the latest on the Deadwing deluxe edition?

Well, I’ve remastered the album. It’s all about the other content really, like the documentary stuff and the interviews. It takes time. I think it’ll be out this year.

Is there a chance of seeing reissues of the Incredible Expanding Mindfuck releases?

I did a box set about five or six years ago of all of that music. For me, it was supposed to be the final definitive word on IEM. There are no plans.

Do you have any updates on the released version of “Anyone But Me?“

All I can tell you is that its coming and that it will be the next release. I can’t tell you a date yet but it should be within the next six weeks.

What do we have to look forward to with your forthcoming book and two new studio albums?

The book is different to most other music books. I thought, “OK, if I’m going to do this, I want to try and do something different.” It’s a book that has everything in it from short stories, to an autobiography, to my thoughts about music, my thoughts about the art of listening to my relationship with my fan base, which is quite the unique and strange relationship. I tried to write about all of these things and knit it all together in a cohesive way. I hope its a bit of an adventure.

The next record I’m doing is a rock album. Its something with the guitar. The one after that is the complete opposite. I’ve already got three or four songs for that album. It’ll be almost completely electronic, very much taking “KING GHOST” as a starting point.

Special thanks to Caroline International, Steven’s management, Tim Bowness and Anil Prasad for their help and guidance through this process.